REVIEW ARTICLE

Insight into Erythrina Lectins: Properties, Structure and Proposed Physiological Significance

Makarim Elfadil M. Osman, Emadeldin Hassan E. Konozy*

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2017Volume: 5

First Page: 57

Last Page: 71

Publisher Id: TOBCJ-5-57

DOI: 10.2174/1874847301705010057

Article History:

Received Date: 23/06/2017Revision Received Date: 19/10/2017

Acceptance Date: 22/10/2017

Electronic publication date: 14/11/2017

Collection year: 2017

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode). This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

The genus Erythrina, collectively known as “coral tree”, are pantropical plants, comprising of more than 112 species. Since the early 1980s, seven of these have been found to possess hemagglutinating activity, although not yet characterized. However, around two dozen galactose-binding lectins have been isolated and fully characterized with respect to their sugar specificity, glycoconjugates agglutination, dependence of activity on metal ions, primary and secondary structures and stability. Three lectins have been fully sequenced and the crystal structures of the two proteins have been solved with and without the haptenic sugar. Lectins isolation and characterization from most of these species usually originated from the seeds, although the proteins from other vegetative tissues have also been reported. The main objective of this review is to summarize the physicochemical and biological properties of the reported purified Erythrina lectins to date. Structural comparisons, based on available lectins sequences, are also made to relate the intrinsic physical and chemical properties of these proteins. Particular attention is also given to the proposed biological significance of the lectins from the genus Erythrina.

1. INTRODUCTION

The family Fabaceae [Leguminosis] is considered the third largest family of the flowering plants, with around 800 genera and 20,000 species [1]. The genus Erythrina belongs to the legume group, which is widely distributed along the tropical and subtropical areas of the world. Many phytochemical compounds such as alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins and lectins have been isolated from this genus and received special attention in research and biotechnology. Lectins are defined as plant proteins possessing at least one non-catalytic domain that binds reversibly to specific mono or oligosaccharides [2]. The history of plant legume lectins began in 1890, after the discovery of the toxic robin from the barks of the black locust tree Robinia pseudoacacia [3]. The genus Erythrina was not subjected to lectin investigation until sixty years later, when the first two species Erythrina bogotensis and Erythrina galuca were reported by Maleka [4]. At that time, the hemagglutination features of lectins were attributed to their specific carbohydrate binding activity [5]. It was not until the eighties, when the influx of lectins data from different species of Erythrina was obtained as a result of the introduction of modern biochemistry and affinity chromatography techniques, which made the systematic and structural isolation of numerous lectins possible. To date and to the best of our knowledge, only around 34 different Galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine specific lectins from species of Erythrina have been detected and characterized. Initial reports indicated only the mere presence of hemagglutination activity of these proteins as in case of Erythrina falcata and Erythrina guineensis [6, 7]. Later, full report on molecular and structural elucidation of these proteins was available in case of Erythrina corallodendron [ECorL] and Erythrina caristagalli lectins (ECL) [8, 9] (Table 1). In this review article, we attempt to provide a detailed description on lectins from the genus Erythrina, with regards to their isolation, purification, and characterization, with special focus on their biochemical, biophysical, physiological and structural characteristics compared to related lectins from other legume genera.

| Source | Lectin | Source | Lectin |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. abssynicia | EAbsL | E. indica leaves | EILL |

| E. americana | EAL | E. indica seeds | EISL |

| E. arborescens | EArbL | E. latissima | ELatL |

| E. berieroma | EBerL | E. lithosperma | ELitL |

| E. bogotensis | EBL | E. lysistemon | ELysL |

| E. caffra | ECafL | E. poeppiginiana | EPoeL |

| E. caristagalli | ECL | E. perrieri | EPL |

| E. corallodendron | ECorL | E. rubrinervia | ERL |

| E. costaricensis | ECosL | E. senegalensis | ESenL |

| E. edulis | EEL | E. speciosa | ESpecL |

| E. falcata | EFalL | E. steyermarkii | ESteL |

| E. flabelliformis | EFL | E. stricta | ESL |

| E. fusco | EFucL | E. suberosa | ESubL |

| E. glauca | EGlaL | E. sumatrana | ESumL |

| E. globocaliz | EGL | E. variegata | EVL |

| E. guineensis | EGuiL | E. velutina | EVA |

| E. humena | EHL | E. vespertilio | EVesL |

| E. zeyheri | EZL |

2. OCCURENCE AND PURIFICATION

Galactose-specific lectins from Erythrina (ELs) were isolated mainly from seed extracts; in some studies they were isolated from other vegetative parts such as leaves, barks, nods and pods. In all reported studies, the extraction methods were achieved with saline and/or saline buffered solutions. In some cases, the method proceeded by a de-fatting step to ensure removal of lipids and pigments. The yield of the purified lectins varied from less than 1%, as in case of E. arborescens and E. senegalensis [10, 11] to as high as 90% as in E. americana [12]. The reason behind these variations was ascribed to the use of human stroma O-RBCs- Sephadex resin, as it is believed that lectins possess higher affinity toward complex glycans than simple mono or disaccharides [13]. Seed lectin content varied between the different Erythrina species; for example E. suberosa seeds contain only 2 mg lectin per 100 g seeds flour, while around 1540 mg lectin per 100 g seeds was purified from E. variegate [14] (Table 2). Around 2-3 lectin isoforms were detected by isoelectric focusing (Table 3), which were in coherent with other legume lectins. The occurrence of multiple isolectins in legume seeds seems to be related to physiological roles, though yet to be clearly disclosed, and could be extended to include plenty of other plant families such as Cucurbitaceae [15-17]. The use of affinity matrices leads to the purification of all isolectins into a single homogeneous peak. However, separation of these isoforms would have been achieved if a salting-out fractionation step use ammonium sulfate [0-40%, 40-60% and 60-80% respectively] was introduced in the purification procedure, as in case of E. abyssinica lectins, where three galactose specific lectins were isolated [18]. Vegetative tissues from legume lectins would also contain more than one lectin, which may differ from seed lectins (e.g. bark lectins from Sophora japonica) [19]. In case of E. indica leaf lectin (EILL), a single lectin could be detected, which differs from its counterpart seed lectin (EISL) with regard to native molecular weight, isoelectric point and several other physiochemical properties. It is, however, yet to be determined if the protein is encoded by the same gene as the seed lectins [20].

| ELs |

Conc. [mg/100g flour] |

Yield [%] |

Specific Titer[HUA/mg1] | Affinity Medium | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAL | 49 | 91 | 28.51 | Human Stroma O RBCs-Sephadex-25G | [12] |

| EArbL | 40 | 0.23 | 7.8 | Acid treated ECD-Sepharose-6B | [10] |

| ECafL | 133-166 | 65-80 | UA | Lactose-divinylsulphone activated Sepharose-4B | [58] |

| ECL | 166-180 | 74-75 | 210 | Con A-Sepharose | [21] |

| ECorL | 125-166 | 50-70 | UA | Lactose-divinylsulphone activated Sepharose-4B | [58] |

| ECosL | 103 | UA | 75.4 | O-α-D-galactosyl polyacrylamide | [22] |

| EEL | 121 | UA | 57.1 | O-α-D-galactosyl polyacrylamide | [24] |

| EILL | 0.63 | UA | 37200 | Lactamyl-Seralose-4B | [20] |

| EISL | 120 40 |

UA UA |

UA UA |

O-α-D-galactosyl polyacrylamide Acid treated ECD-Sepharose-6B |

[80] [10] |

| ELatL | 100-117 | 60-70 | UA | Lactose-divinylsulphone activated Sepharose-4B | [58] |

| ELitL | 40 | UA | UA | Acid treated ECD-Sepharose-6B | [10] |

| ELysL | 5.1 167-200 |

40 60-75 |

75 UA |

Lactose-Agarose Lactose-divinylsulphone activated Sepharose-4B |

[34] [58] |

| ERL | 152 | UA | 86.79 | O-α-D-galactosyl polyacrylamide | [23] |

| ESenL | 6.22 | 0.5 | 9.83 | Lactose-Sepharose-4B | [11] |

| ESpecL | 250 | 66 | 773 | Lactose-Sepharose-4B | [25] |

| ESubL | 2 | UA | UA | Acid treated ECD-Sepharose-6B | [10] |

| EVL | 540 1540 |

43 83.8 |

64 434.4 |

Acid-treated Sepharose-6B Lactose-Sepharose-6B |

[39] [14] |

| EVesL | 220 | UA | UA | Lactose-Sepharose-6B | [39] |

3. PHYSIOCHEMICAL AND ANALYTICAL CHARACTERISTICS

3.1. Biophysical Characteristics

Legume lectins are essentially metallo-proteins and Erythrina lectins are no exception, they are all Ca2+ and Mn2+- dependent proteins. Demetallization of the protein has shown that not all tested lectin activities were affected by the presence of chelating agent (50 mM or 100 mM EDTA). This suggests that the metal ions might be buried deep inside the lectin structure and might not affect the binding of the saccharide conjugates. Examples of such lectins are from E. indica, E. caristagalli, E. edulis, E. rubrinervia, and E. americana [10, 12, 21-24] (Table 3). Almost all tested Erythrina lectins were not affected by the presence of EDTA with the exception of E. speciosa and E. senegalensis, where complete inactivation was observed when the protein was treated with chelating agent. The activity of the protein was restored when both Ca2+ and Mn2+ were added [11, 25]. To emphasize the role of the metal ion in legume lectins, it is found that the binding of the sugar moiety relies on the simultaneous presence of Ca2+ and a transition metal ion, Mn2+ as in our case. This might be explained by the ability of the calcium ions to stabilize the carbohydrate binding via structural water molecules. The structural analysis of ECorL and ECL showed that each metal ion is attached to four extremely conserved residues and two water molecules. The calcium ion binds Asp129, Phe131, Asn133 and Asp136, while the manganese ion binds Glu127, Asp129, Asp136 and His142. The two aspartate residues form a bridge between the two metal ions [9, 26, 27]. Other residues such as Trp135 are believed to be required for the tight binding of Ca2+ and Mn2+ to the lectin. This was confirmed by site directed mutagenesis, where mutant-ECorL (W135A) in which Trp135 was replaced by Ala135, resulted in loss of the metal ions upon dialysis and rendered the mutant protein inactive [28]. The structural role of metal ions was studied on the demetalized concanavlin A (Con A) structure, refined at 2.5Å and its subsequent metal ions activation. The study showed that binding of calcium and zinc/cobalt ions is controlled by the key event isomerization of the peptide bond Ala207-Asp208 from trans to cis, and the formation of the transitioned Ca2+ binding site by the side chain residues of Glu8, Asp10 and His24. In case of W135A, the release of metal ion occurs due to the increased mobility of the 132-136 loops rather than being coupled directly to the isomerization process observed for Con A. Binding of Zn2+ or Co2+ in Con A initiates the movement of Asp19 and alters the disordered Pro13-Pro23 loop that result in transforming the lectin from “unlocked” metal free state into “locked” metals bound form, hence enabling carbohydrate recognition [29, 30]. It was also proposed that the presence of high sugar concentration in the absence of metal ions stabilizes the unlock conformation and shift it toward a lock conformation that has higher degree of folding [31], which may be extended to explain in part how binding the monosaccharide can protect against chemotropic exposure. It is noteworthy to say that binding sugar moiety i.e. galactose, to both ECL and ECorL does not bring any conformational change of the D-loop within the binding site of the metalized protein unlike Con A. Hence, the structural effect of the carbohydrate binding to the demetalized ELs remains to be investigated.

Lectins are known for their high stability under harsh conditions. Erythrina lectins retain full activity upon exposure to buffer solutions ranging in pH from 6-10. However, at pH 11, the protein is completely inactive and in acidic buffer solutions, the proteins retain only around 25% activity [11, 14, 20, 25]. On the other hand, full activity was observed in the pH range of 2-10 for E. indica, E. poeppigiana and E. steyermarkii lectins [10, 32]. Konozy et al. investigated the effect of pH on Erythrina lysistemon lectin (ELysL) secondary structure by using Circular Dichroism (CD). It was found that a wide range of conformational changes occurred within the pH range tested. The maximum secondary structure was observed at pH 8.0 and the minimum at pH 2.0 [33]. Thermal studies on some of Erythrina lectins showed that they were stable at wide range of temperatures, up to 70oC as in the case of ELysL [34]. In general, most of the tested lectins were stable up to 50oC and rapidly lose their activity to the point of complete abolishment upon reaching the next temperature thermo interval (Table 3). The high stability of lectins might be attributed to the proteins glycosylated, and evidence suggested that glycosylation elevates numerous physical protein instabilities, which occur upon exposure to extreme environmental conditions. Studying the role of glycosylation using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations on the structure of E. corallodendron glycosylated-native and N-glycan devoid-recombinant lectins (nECorL and rECorL) showed that glycosylation provides higher thermal stability to nECorL because it affects the side-chain packing of the lectin. This leads to reduction of non-polar solvent accessibility of surface area (ASA) of nECorL compared to rECorL, hence the marginally higher stability [35].

| ELs |

NativeMr♠ [kDa] |

ProtomerMr* [kDa] |

pI | ε1cm1% |

Metal Ion [atom/mole] |

pH |

T [oC] |

N. Sugar [%] |

Ratio of Natural N-Glycan | Ref. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca+2 | Ma+2 | Man | GlcNAc | Xyl | Fuc | Gal | Arb | |||||||||

| EAL | 57 | 30 | 6.3, 6.6 | 26.42 | UA | UA | UA | 25-50 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | - | - | [12] |

| EArbL | UA | 28 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | 5.7 | UA | UA | UA | UA | - | - | [10] |

| ECafL | 59.3 | 30 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | 5.6 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1 | - | - | [58] |

| ECL | 56.8 | 27, 28 | UA | UA | 1.9 | 1 | UA | UA | 4.5 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 1 | 1 | - | - | [21] |

| ECorL | 60.5 | 28 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | 5.5 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 1 | 1 | - | - | [58] |

| ECosL | 56 | 27.2 | 6.48, 6.84, 6.97 | 26.42 | 5-6 | UA | UA | UA | 3.64 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [22] |

| EEL | 56 | 27.5 | 5.4, 5.5 | UA | 6-7 | traces | UA | UA | 7.8 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [24] |

| EFL | UA | 29 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [58] |

| EFucL | UA | 28 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [81] |

| EGL | UA | 28 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [81] |

| EHL | UA | 29 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [81] |

| EILL | 58 | 30, 33 | 7.6 | 12.5 | UA | UA | 7 | 25-55 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [20] |

| EISL | 68 | 30, 33 | 4.83,5.09, 5.44 |

UA | 2.9-3.5 | 1.8-2.3 | 3-9 | 25-50 | 4.5 | 8.8 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 3 | 1.7 | 3.3 | [10] |

| ELatL | 61.98 | 32, 33 | UA | UA | UA | UA | 7.5-10.5 | 25-70 | 9 | 3 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1 | - | - | [58] |

| ELitL | UA | 26, 28 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | 4.1 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [10] |

| ELysL | 58 | 30 | 5.2- 5.8 | 17 | UA | UA | 7.5-10.5 | 25-70 | 6.2 | 3 | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | - | - | [34] |

| EPoeL | 50 | 21, 25 | UA | UA | UA | UA | 2-10 | 40-70 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [32] |

| EPL | 29, 30 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [58] | |

| ERL | 62 | 29.5 | 5.19, 5.02, 5.12 | 16.04 | 16 | 1 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [23] |

| ESenL | 62 | 30 | UA | UA | UA | UA | 6-10 | 25-65 | 6.5 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [11] |

| ESpecL | 58 | 27.1 | 5.8, 6.1 | 14.5 | UA | UA | 6- 9.6 | 25-65 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [25] |

| ESteL | 50 | 25 | UA | UA | UA | UA | 2-10 | 40-70 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [32] |

| ESL | UA | 28 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [53] |

| ESubL | UA | 28 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | 6.8 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [10] |

| EVL | 60 | 33, 35 | UA | UA | UA | UA | 6-9 | 25-60 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | - | - | [14] |

| EVesL | 59 | 32 | 4.8, 5.3 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | 9.7 | 7.5 | 2 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 12.5 | - | [39] |

| EZL | UA | 29 | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | [58] |

3.2. Molecular Mass and Sequence Analysis

ELs are assembled from one chain protomer of molecular weight ranged between 27 to 35 kDa, which in turn form a dimer of native molecular weight 56-68 kDa. In most cases, the protomers are identical, however hetero dimers are also common (Table 3). The heterogeneity of the subunits’ molecular masses occurs due to differences in the primary structure and/or the variation in the number of the N-glycan chains attached and their structural composition. The chemical structural differences between isolectins were extensively studied on EVLs. Yamaguchi and his colleagues attributed the difference to the substitution at seven amino acids between A-subunit Mr 35 kDa (Gly30, Asn46, Glu71, Tyr106, Val111, Glu202 and Glu206) and B-subunit Mr 33kDa (Asp30, Asp46, Gln71, Ser106, Ile111, Gln202 and Gln206). However, upon treatment with the deglycosylating agent trifluoromethanesulfonic acid, both subunits’ molecular weights were decreased to 31 kDa, which was explained by the loss of the glycan chains [36]. The single polypeptide chain of ELs protomer is composed of 230-294 amino acid residues, which again are within the range of amino acid compositions of legume lectin. Structurally, all ELs are rich in acidic, hydroxyl and aliphatic amino acids residues, with low content of methionine (4-8 residue/Mole lectin) and no cysteine residues, except in the case of E. rubrinervia lectin (ERL), where 8 residues per mole lectin is reported [23] (Table 4). All purified Erythrina lectins reported so far exhibit similar physicochemical properties. They share similarities in the N-terminal amino acid sequences. 16 out of the 18 available sequences of the primary structure of lectin have valine as the first amino acid residue. Only two species display alanine in the N-terminus amino acid. It is to be noted that glutamine and threonine are conserved at position 2 and 3 of the N-terminal sequence (Table 5).

3.2.1. The Exceptional Erythrina lysistemon Seed Lectin

Although the sequence/structure of E. lysistemon lectin (ELysL) remained to be elucidated, ELysL showed few but clear distinctive features that deviate from its ELs counterparts. All ELs exist in dimeric forms, mainly consist of β-sheets and loops, and lack the ability to bind ligands other than the carbohydrates. Regardless of the similarities in physiochemical properties, the amino acid composition profile and N-terminal identity match the related ELs. ELysL can exist both as dimer and tetramer with molecular weights of 58 and 120 kDa respectively. At physiological conditions the higher concentration of the former predominates. This is a distinctive feature observed in Con A and Tamarindus indica lectin EMtL [16, 34], that indicates the presence of tetramer interface motifs. ELysL is also distinguished due to its high α-helices secondary structure content. Denaturing studies monitored by CD and hemagglutination assays indicated that the unfolding event of ELysL is not a two state process as with ECorL. However, it includes an intermediate molten globule-like structure that retains around 80% of activity. Fluorescence and amino acid modification studies indicated that tryptophan did not display any role in binding sugar, a feature shared by EILL [20] and EspecL [25]. In the case of ELysL, tryptophan is located within a hydrophobic region that is designated for adenine binding. Although ECorL and Con A possess the sequence for adenine binding, the ability for such ligand binding remained exclusive to ELysL among ELs. Such characteristic feature is also shared by other adenine binding lectins, such as winged bean agglutinin [WBA-I and WBA-II] and the tetramer Dolichos biflorus lectin (DBL), where the α-helix in the protein 3D structure forms a hydrophobic site by direct overlap between the two monomers of the lectin [33, 37, 38].

4. STRUCTURE OF ERYTHRINA LECTINS

4.1. N-Glycan Structure

All reported ELs are glycoproteins (natural sugar content 3.6-10%) (Table 3). The N-glycan attached to the lectins is composed mainly of a complex combination of Mannose, Xylose, Fucose and N-acetyl-glucosamine with different ratios and orders. However, the presence of Galactose was reported in E. vespertillo lectin [39] while Arabinose and Galactose were detected in E. indica lectin glycan composition [10] (Table 3). In some studies, Con A was used to determine if the non-reduced terminal of N-glycan is a D-mannose, and was used to purify lectins in some cases [22, 34]. The presence of Xylose is believed to be a signature for plant glycoproteins, as it is believed that the glycans of animal proteins lack the Xylose moiety [40]. Ashford et al stipulated that the N-linked glycan of ECL is characterized firstly by the substitution of the common core of the pentasaccharides [Manα3-[Manα6]-Manβ4NAcGlcβ4NAcGlc] of N-glycoproteins by β-D-Xylose (1→2) attached to the β-mannosyl residue and secondly by the presence of α-L-Fucose (1→3) linked to the reducing end of GlcNAc residue. About 90% of the branched N-glycan was of the following sequence [α-D-Man[1→3]α-D-Man[1→6]]-β-D-Xyl-[1→2]-β-D-Man-β-D-GlcNAc-[1→4]-[α-L-Fuc-[1→3]]-D-GlcNAc [41]. X-ray crystallography studies enabled the generation of an electron density map of the six N-glycan residues out of the seven in the 3D crystal structure of ECL, as the X-ray diffraction resolution was suitable enough to generate such a model [9].

The hepta-N-glycan of ECorL was found to be [α-D-Man(1→3)-[α-D-Man(1→6)]-β-D-Xyl-(1→2)]-β-D-Man(1→4)-β-D-GlcNAc-(1→4)-[α-L-Fuc-(1→3)]-D-GlcNAc], and the heterogeneity of the oligosaccharide moieties occurs due to the lack of Fucose in some of the chains attached to ECorL [42, 43]. The glycosylation site is confined to three amino acid residues, namely Asn17, Asn46 and Asn113. The probable site for attachment of N-glycan to ECL is Asn113, while ECorL and EVA (E. velutina lectin) have two glycosylation sites, the Asn17 and Asn113 in each protomer. However, the crystal structure of ECorL illustrated only the N-glycan joined to Asn17, and the side-chain of this site is structurally compensated by the conformational changes and the formation of hydrogen bonds in rECorL, without affecting the backbone of the site. On the other hand, the three EVL isolectins [with A and B protomers] have different glycosylation patterns and sites. The A-subunit is glycosylated at Asn17, Asn46 and Asn113, whereas the B-subunit is glycosylated at only two sites, Asn17 and Asn113 due to the substitution of Asn47 by Asp47 [9, 27, 36]. Molecular dynamic simulation on ECorL showed that the N-glycan is very mobile, interacts predominantly with the solvent, and it can also form transient non-covalent interaction with the protein surface, at distant amino acids residues (Lys55 and Tyr53), allowing more flexibility of the loops [35, 44-46].

4.2. 3D Structure

Legume lectins by definition are a family of proteins, which have the same tertiary and importantly variable quaternary structure. X-ray crystallography studies of Erythrina lectins started in 1987 when X-ray diffraction pattern studies were performed on ECorL [46]. This was followed by other successful crystallization and structure determinations of both ECorL and ECL.

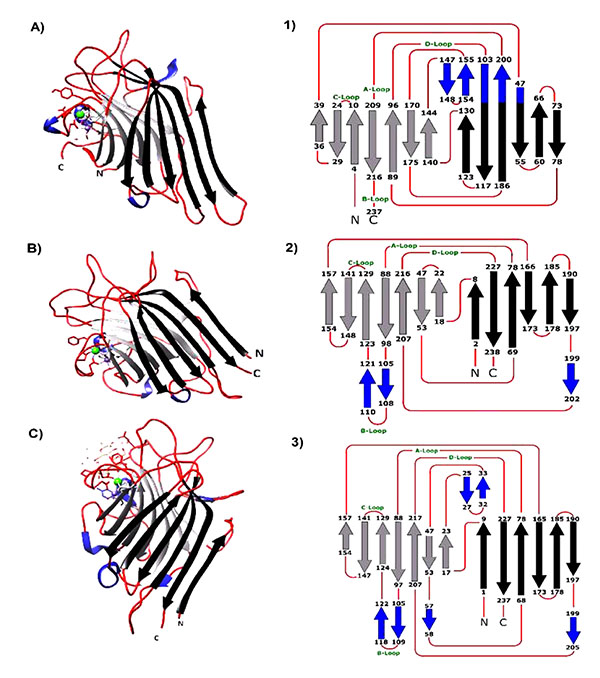

ELs, like all other legume lectins are strictly composed of anti-parallel β-sheets, loops, and no α-helices, which form a structure known as “jelly roll”. The β-sheets are divided into three groups, six standard flat back sheets, seven standard curved front sheets and three-to-five small S sheets. In both ECorL and ECL, the first and second back β-sheets are connected and formed via N- and C-terminals. Conversely, the N- and C-terminals of Con A are formed by the front β-sheets. The loops are constructed by around 51% of the total amino acids residues. The main hydrophobic core is located between the front and back sheets and a second hydrophobic nucleus is generated between the front sheets and the extended three loops, forming the metal ion binding site as well as the carbohydrate recognition domain (Fig. 1) [8, 9]. Erythrina lectins possess a unique mode of quaternary association different from the canonical mode of dimerization seen in Con A, or any other legume lectins. They can only exist in the form of dimers linked via handshake association. Such, mode of association was first seen in ECorL and hence called “ECorL-Type”. Many attempts have been made to identify the characteristics of the dimer interface. Elgavish and Shaanan report that the legume lectin dimer is established and stabilized by the chemical composition of the amino acids present in the dimer interface rather than the sequence of the amino acids [47]. Using a graph-spectral algorithm to identify the side-chains and their cluster centers in combination with the traditional multiple sequence alignment indicated that the quaternary mode of association in legume lectins could be determined by their sequence. The ECorL-type of dimerization has an interface called X3 that allows the overlap of the β-sheets of each monomer to form the handshake. Mapping the structurally conserved residues identified in the X3 interface cluster revealed that both SFE and VIKYD motifs located at positions 60-70 and 170 of the amino acid sequence are responsible for the association. ECorL exclusively exists as a dimer and cannot form a tetramer because its sequence lacks the interface determinants at the N- and C-terminals that allow the tetramer formation [48]. It was proposed earlier that the hindrance of the canonical dimer formation in ECorL was due to the glycosylation at Asn17 of the protein N-terminal. However, since other lectins such as ECL, WBA-I and WBA-II exhibit the same handshake mode of dimerization but with a different glycosylation site far from the tetramer interface motifs, it was concluded that the ECorL-type of dimerization occurs due to protein intrinsic factors [9, 44, 49, 50]. Further analysis of the native and recombinant ECorL crystal structures indicated that there is no significant difference except the absence of the N-glycan in rECorL. Both adopt the handshake dimerization, in fact glycosylation only affects the overall thermal stability of the nECorL over the rECorL, not the dimerization properties.

4.3. Carbohydrate Binding and Sugar Specificity

Binding of carbohydrate to lectins is attributed to a shallow groove located on the surface of the molecule known as the carbohydrate binding domain “CBD”. ELs are classified as Hololectins which contain two identical or very similar binding sites [51]. ELs are basically Galactose/Galactose derivative specific lectins (Table 6). The structural features of carbohydrate recognition in ELs were determined from several X-ray crystal structures of both ECorL and ECL, native, recombinant and mutant models. In brief, the CBD is formed by four loops (A, B, C and D) [52]. Loops A, B and C contain the highly conserved residues (Ala88, Asp89, Gly107 and Asn133) which form the binding site of carbohydrate in legume lectin, while loop D is highly variable and its amino acid residues determine the carbohydrate specificity of each lectin. Unlike Man/Glc specific lectin, binding of sugar moieties to ECorL does not induce any conformational change in loop D owing to the presence of water molecules, which would be replaced by a hydroxyl group of the incoming ligand.

Although the binding of lactose to ECL is mediated via different structural arrangements than ECorL [9], the obtained crystals of ECorL in complex with mono and disaccharides reveal that the sugar recognition is taking place in the same manner, with a slight difference presented in additional formation of one direct hydrogen bond and an extra Van der Waals interaction are required when binding Lactose/ N-acetyllactosamine [27]. On the other hand, the structural/thermodynamic relationship studies performed in ECorL binding to disaccharides offer a great number of binding options compared to monosaccharides, which can’t be detected in the X-ray static model [53].

For further studies on the importance of the affinity site amino acids in ECorL, which are likely to affect the affinity and/or the specificity of lectin towards certain sugar moieties, a series of engineered mutant lectins were achieved. The same hemagglutinating activity and affinity towards galactose were obtained after substituting Tyr108 and Pro134-Trp135 residues with equivalent peptide residues found in the peanut agglutinin PNA affinity site (Thr108 and Ser-Glu-Tyr-Asn) and soybean agglutinin SBA (Ser-Trp) [54]. Lower affinity towards GalNAc and almost no affinity for Methyl-β-D-dansylgalactosaminide [MeβGalNDns] are noticed in mutants with the PNA substitution peptide. These results suggest that the differences in sugar specificity between ECorL, SBA and PNA are due to the steric hindrance caused by the additional amino acids found in PNA [55]. According to Adar and her colleagues, Trp135 plays a vital role in enhancement of the affinity binding of lectin to MeαGalNDns [28]. Mutation at position 219 showed that the native Gln219 side-chain provides a conformational flexibility that allows several favorable interactions with LacNAc, hence enhancing the binding affinity [56]. Testing the hemagglutinating activity of the T106G mutant and the subsequent crystallization of lectin with Gal/GalNAc showed remarkable reduction of the lectin affinity towards galactose and, to the contrary, enhancement of GalNAc affinity, these findings are explained by the formation of an additional direct hydrogen bond between GalNAc and the adjacent Gly107 [57].

5. GLYCOCONJUGATES AND CELL TYPING

Despite the overall physiochemical and the structural similarities between lectins isolated from different species of the genus Erythrina, their ability and extent to which they agglutinate cells and glycoconjugates varies. Most of them agglutinate human RBCs and in some cases display more affinity toward certain blood types [10, 58]. While many of them can agglutinate rabbit erythrocytes, their ability to agglutinate other animal blood cells varies drastically [23, 24]. Although agglutination against protease-treated RBCs provided better accessibility to the bound membrane glycoconjugates and enhanced the binding affinity of lectins by several folds, their agglutination affinity remained the same. In this context, it is to be noted that the best hapten inhibitor might differ from the membrane bound saccharide receptor recognized by lectin. Hence, many attempts have been made to redefine the carbohydrate specificity of ECorL and ECL, which has been achieved and extended to higher affinity binding of glycoconjugates with the polyvalent terminal glycoepitops Galβ1-4GlcNAc and Fucα2Galβ4GlcNAcβ- [13, 56, 59]. Agglutination occurs when a homogenous carbohydrate-lectin cross-linked precipitate is formed between lectins and multivalent glycosides bearing a specific sugar, such as LacNAc [60]. This process can be influenced by many factors including the relative amount of the bi, tri, and tetraantennary carbohydrate on the cell surface, which determines the valency of the carbohydrate. Moreover, the size of the lectin monomer is also considered an influencing factor for the oligosaccharide valency. Hence, the chain length in biantennary molecules can determine whether tetravalent lectins such as SBA and Con A can form a precipitation complex, and in return has no effect when it comes to divalent lectins such as EIL, EArbL and Ricinus communis agglutinin-I [RCA] [61]. For the divalent lectins and unlike Con A, the presence of bisecting GlcNAc in the biantennary complex-type oligosaccharides has little or no effect on the binding activity and the valencies of the carbohydrate [62, 63]. In a mixture of divalent Erythrina lectins, unique lattices with tri- and tetra-antennary complex-type oligosaccharides are formed with almost the same affinity but different stability. Comparison of the nECorL with rECorL provides evidence for a heterotypic carbohydrate-carbohydrate interaction between the N-glycan of ECorL and the triantennary glycoprotein, which has led to the stabilization of a specific lectin-carbohydrate cross-linked complex that cannot be formed by rECorL [64].

|

Fig. (1). A, B and C are the monomers of Con A, ECorL and ECL crystallized with hapten ligand [pdb files: 1c57, 1axy and 1gzc respectively]. The 3D- monomer structures were opened and edited using UCSF-Chimera 1.8 software [1-3]. are the topology diagram of each lectin deduced from the 3D-structure from each lectin. Black arrows represent the β-back black sheets, the light gray arrows represent the β-front sheets and the small blue arrows are the S-sheets while the red lines represent the loops. A, B, C, and D-loops contains the amino acids responsible for sugar binding. |

|

Amino Acid [Residue/Mole] |

Erythrina sp. Lectin | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAL | ECafL | ECL | ECorL | ECosL | EEL | EFL | EHL | EILL | EISL | ELatL | ELysL | EPL | ERL | ESenL | ESL | EVL | EVesL | EZL | |

| Asp | 33 | 62 | 62 | 60 | 57 | 52 | 61 | 62 | 69 | 63 | 62 | 62 | 66 | 65 | 64 | 58 | 96 | 65 | 63 |

| Glu | 25 | 58 | 55 | 58 | 63 | 49 | 57 | 60 | 63 | 61 | 55 | 59 | 50 | 64 | 62 | 53 | 58 | 52 | 60 |

| Ser | 38 | 49 | 47 | 47 | 53 | 35 | 46 | 48 | 41 | 51 | 50 | 51 | 45 | 71 | 53 | 57 | 44 | 48 | 48 |

| Gly | 48 | 41 | 39 | 41 | 50 | 32 | 39 | 41 | 50 | 38 | 41 | 41 | 36 | 47 | 40 | 40 | 36 | 40 | 39 |

| His | 3 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| Arg | 14 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 11 | 14 | 8 | 13 | 12 |

| Thr | 40 | 41 | 43 | 41 | 44 | 33 | 44 | 42 | 48 | 44 | 38 | 39 | 38 | 28 | 45 | 43 | 42 | 43 | 43 |

| Ala | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 42 | 33 | 46 | 40 | 57 | 40 | 39 | 41 | 43 | 22 | 45 | 36 | 40 | 43 | 40 |

| Pro | 47 | 36 | 39 | 39 | 37 | 36 | 36 | 34 | 44 | 34 | 37 | 43 | 30 | 23 | 45 | 35 | 12 | 39 | 35 |

| Tyr | 29 | 17 | 20 | 18 | 14 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 21 | 22 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 10 | 19 | 17 | 16 | 20 | 18 |

| Val | 50 | 34 | 42 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 30 | 32 | 39 | 42 | 33 | 32 | 33 | 20 | 36 | 35 | 44 | 44 | 30 |

| Met | 8 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Cys | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ile | 36 | 31 | 30 | 29 | 24 | 20 | 22 | 26 | 35 | 29 | 28 | 28 | 24 | 17 | 32 | 24 | 28 | 31 | 25 |

| Leu | 53 | 37 | 37 | 36 | 34 | 26 | 34 | 35 | 37 | 37 | 39 | 36 | 33 | 18 | 39 | 34 | 34 | 38 | 31 |

| Phe | 35 | 29 | 28 | 28 | 16 | 1 | 32 | 31 | 31 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 30 | 11 | 28 | 34 | 24 | 28 | 31 |

| Lys | 36 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 24 | 89 | 21 | 19 | 26 | 18 | 17 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 29 | 18 | 30 | 22 | 17 |

| Trp | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 13 | 0 | 6 | 9 | 0 |

| Total | 535 | 521 | 527 | 513 | 538 | 498 | 513 | 514 | 588 | 548 | 511 | 526 | 491 | 461 | 579 | 514 | 534 | 553 | 509 |

| Reference | [12] | [58] | [21] | [12] | [22] | [24] | [58] | [58] | [20] | [10] | [58] | [58] | [58] | [23] | [11] | [58] | [14] | [39] | [58] |

| Source | N-terminal Sequence |

Score [bits] |

Identities | Seq. Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | |||||

| ECafL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-P-G-N- | 51.1 | 15/15 | 100 | [58] |

| ECL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-P-G-N- | 51.1 | 15/15 | 100 | [53] |

| ECorL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-P-G-N-D-N-L-T-L-Q-G-D-S-L-P- | - | - | [26] | |

| ECosL | A-E-T-M-S-F-S-F- | 21.8 | 6/7 | 85 | [22] |

| EFL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-P-G-N- | 51.1 | 15/15 | 100 | [58] |

| EFucL | V-E-T-I-S-F-N-F-S-E-F-E-P-G-N-N-D-L-T-L-Q-G-A-A-L-I- | 66.8 | 20/25 | 80 | [81] |

| EGL | A-E-T-M-S-F-S-F-S-Q-F-Q-P-G-N-N-D-L-T-L-Q-G-V- | 54.9 | 16/21 | 76 | [81] |

| EHL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-P-G-N- | 51.1 | 15/15 | 100 | [58] |

| EILL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-A-G-N-D-X-L-T-Q-E-G-A-A- | 56.6 | 18/22 | 82 | [20] |

| EISL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-A-G-N-D-X-L-T-Q-E-G-A-A- | 56.6 | 18/22 | 82 | [20] |

| ELatL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S- | 31.2 | 9/9 | 100 | [58] |

| ELysL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-P-G-N- | 51.1 | 15/15 | 100 | [58] |

| EPL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-K-F-E-A-G- | 38.4 | 12/15 | 85 | [58] |

| ESpecL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E- | 41.8 | 12/12 | 100 | [25] |

| ESL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S- | 31.2 | 9/9 | 100 | [58] |

| EVL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-A-G-N-D-X-L-T-L-Q-G-A-A-L-I- | 66.4 | 21/25 | 84 | [36] |

| EVesL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-A-G-N-D-S-L-T-L-Q-G-A-S-L-P- | 72.7 | 23/26 | 88 | [39] |

| EZL | V-E-T-I-S-F-S-F-S-E-F-E-P-G-N- | 46.9 | 14/15 | 93 | [58] |

| Relative Inhibitory Activity of Erythrina Lectins | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EArbL | ECafL | ECosL | ECL | ECorL | EEL | EFL | EFucL | EGL | EHL | EILL | EISL | ELatL | ELitL | ELysL | EPoeL | EPL | ERL | ESenL | ESpecL | ESteL | ESL | ESubL | EVL | EVesL | EZL | |

| D-Galactose | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | + | + | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| N- Acetyl-D-glactoseamine | 4.0 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 2.5 | + | + | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 2.5 | nT | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.25 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 2.5 |

| Metheyl-α-D- galactoside | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 2.0 | nT | nT | 1.0 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.5 | nT | 1.0 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 2.0 | nT | 2.0 | 2.0 | nT | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Metheyl-β-D- galactoside | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 0.5 | nT | nT | 1.0 | 0.7 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.3 | nT | 1.0 | 2.2 | nT | 1.0 | nT | 0.5 | 1.0 | nT | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| p-Nitrophenyl-α-D-galactoside | 8.0 | 30.5 | NT | 3.4 | 1.6 | nT | 3.5 | nT | nT | 3.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 8 | 2.5 | nT | 1.7 | nT | nT | 5.0 | nT | 1.75 | 2.0 | nT | 10 | 2.0 |

| p-Nitrophenyl-β-D-galactoside | 2.0 | 14 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 3.2 | 8.4 | 7.0 | nT | nT | 10 | 0.5 | 8.0 | 10 | 4 | 6.0 | nT | 7.0 | 8.3 | nT | nT | nT | 6.0 | 4.0 | nT | 20.5 | 8.0 |

| D-Galactosamine | nT | nT | 0.1 | 0.7 | nT | 0.3 | nT | nT | nT | nT | 1.7 | 0.1 | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | NI | 0.1 | nT | nT | nT | nT | 0.3 | nT |

| D-Lactose | 4.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 6.8 | 2.7 | 14.9 | 7.4 | + | + | 4.0 | 5 | 4.0 | 7.5 | 4 | 1.8 | 2 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 40 | 8 | 8 | 4.0 | 1.9 | 8.0 | 3.0 |

| N-acetyllactosamine | NI | 33 | nT | 33.8 | 19 | nT | 35 | nT | nT | 17 | 2.5 | nT | 35 | NI | 20 | nT | 17 | nT | nT | 20 | nT | 35 | NI | nT | nT | 17 |

| D-Raffinose | 0.5 | nT | 0.5 | 1.9 | nT | 0.5 | nT | nT | nT | nT | 1.7 | 1.0 | nT | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | nT | nT | nT | nT | 2.0 | nT | 1.0 | nT | 1.0 | nT |

| D-Melibiose | 1.0 | nT | NI | nT | nT | 1.8 | nT | nT | nT | nT | 1.7 | 2.0 | nT | 1.0 | nT | nT | nT | 3.6 | nT | 2.0 | nT | nT | 2.0 | nT | 2.0 | nT |

| D-Fucose | 0.2 | 0.4 | NT | 0.75 | nT | nT | 0.23 | NI | NI | 0.23 | nT | nT | nT | 0.25 | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | 0.44 | 0.25 | nT | nT | 0.23 |

| D-Xylose | NI | nT | NI | NI | nT | nT | nT | NI | NI | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT | nT |

| References | [10] | [58] | [22] | [21] | [58] | [24] | [58] | [81] | [81] | [58] | [20] | [10] | [58] | [10] | [34] | [32] | [58] | [23] | [11] | [25] | [32] | [58] | [10] | [14] | [39] | [58] |

Since the formation of lectin-carbohydrate lattices provides a high degree of specificity and the glycosylation patterns of many cellular and serum glycoproteins undergo alternation during many cellular processes under pathological and pathogenic conditions, rapid growth of exogenous lectin applications was evident. Many ELs have a mitogenic effect on human peripheral blood lymphocytes but do not stimulate mouse thymocytes and splenocytes [21, 32, 58]. ECL was considered as a marker to monitor glycosylation changes during the differentiation of lymphocytes and embryonic cells [65]. It is also considered as a differentiation marker for increased α-fetoprotein-E2 in hepatocellular carcinoma and other malignancies [66]. It was applied to enrich heterogenic human natural killer (NK) cells via negative selection and was proved to be more effective than using monoclonal antibodies [67], and to differentiate between feline monocytes and lymphocytes [68]. It was also used recently as a natural platform for culture and differentiation of stem cells [69], and suggested as a therapeutic agent that selectively targets neurotoxin A from Clostridium botulinum [70]. EVA was investigated for potential use as a prognostic marker in primary central nervous system tumors [71]. Koley proposed a possible application for ELitL in forensic science as an anti-LH marker that can be applied along with the ABO genotype system to settle paternity disputes [72]. In the agricultural field, EIL was considered a potent anti-insect compound against melon fruit fly, that significantly influences the normal growth, development and metabolism of the fly [73].

6. PROPOSED PHYSIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS

Although the physiochemical and the molecular structure of many legume lectins have been resolved and well understood, elucidation of the exact physiological functions and biochemical mechanisms are still in their infancy stages. During the early days of lectins discovery, they were hypothesized to act as storage proteins. However, the specificity of these proteins for sugars contradicts the previous hypothesis. Legume lectins play different roles, depending on their cellular and tissue localization as well as the plant developmental stage [74]. The main functions of seed legume lectins were thought to help in transportation and packaging, nitrogen fixation and recently, as defense molecules. Erythrina seed lectins and other similar seed legume lectins often reside within the protein bodies along with the hydrolytic enzymes and storage proteins. Alpha-galactosidase, α-mannosidase, N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase and acid phosphatase were found to act as endogenous receptors for EISL under in vitro conditions. Elution of these proteins requires the haptenic sugar [75]. Extraction of lectin from crude seed extract resulted in the sudden drop in some of these enzymes activities, with α-mannosidase being the most affected enzyme. Addition of lectin, at a gradual increment, restored up to 35% of the α-mannosidase activity. Such results were not obtained when ConA was used instead of EiSL. These observations allowed hypothesizing an indirect role of EiSL in facilitating the initial hydrolytic attack upon germination and ultimately the growth of the embryo [76]. Following the germination cycle of E. velutina seeds for 21 days, lectin was characterized by a clear delay in degradation in concomitant with a one fold increase in its activity as opposed to other proteins [77]. A similar study was performed with E. corallodendron seedling to monitor lectin activity during germination, where increase in activity was also evident. However, it was hard to verify if the increase in lectin activity was due to the germination processes, as the protein content was not correlated with lectin activity [78]. A recent study on EAbsL isolectins profile during the seed germination of E. abssynicia, in relation to protein content, provided clues on the predicted role of each of the following isolectins, EAbsL-40, EAbsL-60 and EAbL-80. Both isolectins EAbL-60 and 80 were characterized by slow degradation whereas complete loss in activity of EAbsL-40 was achieved in the first three weeks of germination [79]. Among various interesting observations of plant lectins was the finding that some legume lectins interact more favorably with carbohydrates that were coupled to large hydrophobic or aromatic moieties than the sugar component alone. The subsequent discovery of the presence of a hydrophobic binding site independent of the sugar affinity pocket complicated the opened query on biological role of plant lectins. Besides ConA and Peanut lectin, Erythrina lysistemon seed lectin [ELysL] has also been shown to possess a hydrophobic site which binds adenine through an independent binding site [33]. Considering the overall preliminary studies so far, Erythrina lectins would most likely have crucial physiological role rather than being just transport or storage proteins.

CONCLUSION

The legume lectins are a family of sugar-binding proteins found in plants. Erythrina Lectins, for an example, constitute a distinctive subgroup among the legume lectins. They share similar structural and physicochemical features. However, there are apparent variations in properties such as affinity towards sugars, preference for agglutination of human and animal blood and lastly interactions with hydrophobic molecules. These differences might have an influence on the physiological roles from species to species, although such claim is yet to be drastically validated. Further molecular and structural studies are warranted on other Erythrina Lectins to establish their evolutionary changes and to understand their detailed mechanism of actions.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are base of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful for Dr. Iswarduth Soojhawon, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD 20910, USA, for revising and editing the manuscript.